Physicochemical Properties

| Molecular Formula | C34H32N4NA2O4 |

| Molecular Weight | 606.62 |

| Exact Mass | 606.22 |

| Elemental Analysis | C, 67.32; H, 5.32; N, 9.24; Na, 7.58; O, 10.55 |

| CAS # | 50865-01-5 |

| Related CAS # | 553-12-8 |

| Appearance | Typically exists as solids at room temperature |

| Boiling Point | 1128.9ºC at 760 mmHg |

| Flash Point | 636.6ºC |

| LogP | 1.371 |

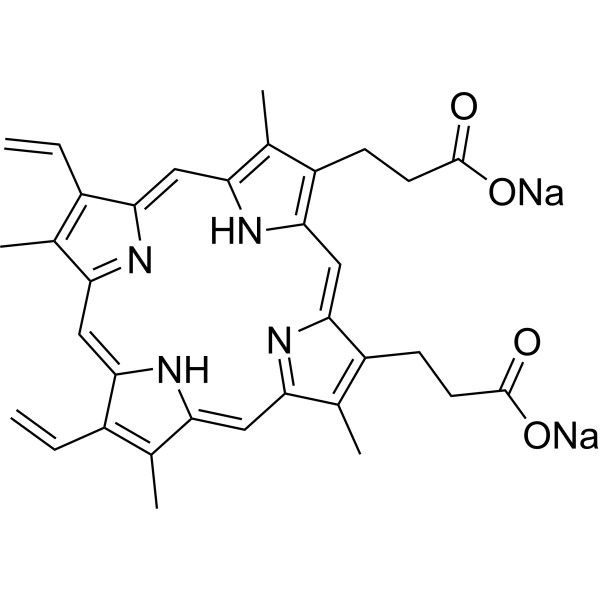

| SMILES | C=CC1=C(C)C2=NC1=CC3=C(C)C(=C(C=C4C(=C(CCC(=O)[O-])C(=N4)C=C5C(=C(C)C(=C2)N5)CCC(=O)[O-])C)N3)C=C.[Na+].[Na+] |

| Synonyms | Protoporphyrin IX (disodium); 50865-01-5; protoporphyrin disodium; Protoporphyrin IX disodium salt; Disodium protoporphyrin IX; Palepron; Protoporphyrin, disodium salt; Protoporphyrin disodium [JAN]; Dojin PM; |

| HS Tariff Code | 2934.99.9001 |

| Storage |

Powder-20°C 3 years 4°C 2 years In solvent -80°C 6 months -20°C 1 month |

| Shipping Condition | Room temperature (This product is stable at ambient temperature for a few days during ordinary shipping and time spent in Customs) |

Biological Activity

| Targets | Endogenous Metabolite |

| ln Vitro |

Protoporphyrin IX disodium (3.6 nmol/g tissue) can induce necrosis of normal rat colon mucosa under light exposure[4]. Protoporphyrin IX disodium (6.6 nmol/g tumor) delays tumor growth after rat tumor irradiation[4]. Protoporphyrin IX disodium (0-25 μM, 2 hours) rapidly leads to increased nuclear G4 levels in Hela cells[5]. Olivo et al. reported that after transurethral resection of higher-grade and higher-stage bladder tumors can produce and accumulate higher levels of Protoporphyrin IX after ALA instillation. Their findings support our results. Miyake and colleagues showed that low expression or molecular defects of ferrochelatase in urothelial cancer correlate with intracellular protoporphyrin IX accumulation. Hagiya and coworkers reported that expression levels of peptide transporter 1 and human ATP-binding cassette transporter 2 play key roles in ALA-induced protoporphyrin IX accumulation. Ogino et al. reported the stimulation of ALA-induced protoporphyrin IX accumulation in T24 cells by a ferrochelatase inhibitor and a human ATP-binding cassette transporter 2 inhibitor. Several factors seem to be involved in the mechanisms underlying the increased accumulation of Protoporphyrin IX in high-grade tumors. Which factor plays the predominant role is a subject of future research.[1] Mammalian porphyrins are generated from δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) through several consecutive enzymatic reactions to Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX), which is further complexed with an iron cation to produce heme or its derivative hemin [5]. |

| ln Vivo |

Three hours after administration of aminolevulinic acid (300 mg/kg, single intravenous injection), the highest levels of Protoporphyrin IX disodium were found in the liver and intestine (approximately 6.3 nmol/g tissue), followed by the aorta (4.3 nmol/g tissue) and esophagus (2.1 nmol/g tissue)[4].

Limited depth of penetration significantly limits photodynamic therapy of nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) using topical delta (5)-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). To demonstrate safety and efficacy of orally administered ALA in inducing endogenousProtoporphyrin IX (PpIX) production in BCC, 13 patients with BCC ingested ALA in a dose-escalation protocol. All dose ranges (10, 20 or 40 mg/kg single doses) resulted in formation of Protoporphyrin IX/PpIX in human skin and BCC, measurable by in vivo fluorescence spectrophotometry. The Protoporphyrin IX/PpIX fluorescence peaked in tumors before normal adjacent skin from 1 to 3 h after ALA ingestion. Gross fluorescence imaging of ex vivo specimens revealed greater PpIX fluorescence in tumor than normal skin only at the 40 mg/kg dose. Fluorescence microscopy confirmed this finding by showing distinct, full-thickness PpIX fluorescence in all subtypes of BCC only after ALA given at 40 mg/kg. Side effects were dose dependent and self limited. Photosensitivity lasting less than 24 h and nausea coinciding with peak skin PpIX fluorescence occurred at 20 and 40 mg/kg doses. After 40 mg/kg ALA, serum hepatic enzyme levels rose to a maximum within 24 h, then resolved over 1-3 weeks. Transient bilirubinuria occurred in two patients. [3] In this study, the biodistribution of 5-aminolaevulinic acid (ALA) and accumulation of Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) in rats have been examined. Two groups of 21 WAG/Rij rats are given 200 mg/kg ALA orally or intravenously. Six rats serve as controls. At 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12 and 24 h after ALA administration, ALA and porphyrin concentrations are measured in 18 tissues and fluids. Liver enzymes and renal-function tests are measured to determine ALA toxicity. In both groups ALA concentration is highest in kidney, bladder and urine. After oral administration, high concentrations are also found in duodenal aspirate and jejunum. Mild, short-lasting elevation of creatinine is seen in both treatment groups. Porphyrins, especially Protoporphyrin IX/PpIX, accumulate mainly in duodenal aspirate, jejunum, liver and kidney (> 10 nmol/g tissue), less in oesophagus, stomach, colon, spleen, bladder, heart, lung and nerve (2-10 nmol/g tissue), and only slightly in plasma, muscle, fat, skin and brain (< 2 nmol/g tissue). In situ synthesis of porphyrins rather than enterohepatic circulation contributes to the PpIX accumulation. Confocal laser scanning microscopy shows selective porphyrin fluorescence in epithelial layers. Peak levels and total production of porphyrins are equal after oral and intravenous ALA administration. In conclusion: administration of 200 mg/kg ALA results in accumulation of photosensitive concentrations of Protoporphyrin IX/PpIX, 1 to 6 h after ALA administration, in all tissues except muscle, fat, skin and brain. Knowledge of the time-concentration relationship should be helpful in selecting dosages, routes of administration and timing of ALA photodynamic therapy [4]. |

| Cell Assay |

Photodynamic detection of Protoporphyrin IX in exfoliated bladder cancer cells [1] ALA-treated and ALA-untreated urine sediments in each chamber were tested for Protoporphyrin IX fluorescence using a spectrophotometer at the appropriate settings (excitation wavelength 405 nm, emission wavelength 550–700 nm, gain 160). The gain of the spectrophotometer was adjusted when the sample intensity was out of range. The spectrum of samples treated with ALA from bladder cancer patients showed a peak at 635 nm, whereas that of ALA-untreated samples did not show such a peak (Fig. 2a). The peak was undetectable in samples from control patients (Fig. 2b). Evaluation of Protoporphyrin IX in exfoliated bladder cancer cells [1] To evaluate the peak at 635 nm, the difference between the intensity of ALA-treated and ALA-untreated samples was calculated. The area under the curve, sensitivity, and specificity of this analysis were 0.68, 60%, and 65%, respectively. As mentioned, the gain was adjusted when the intensity of the sample was out of measurement range. Thus, the calculated difference was divided by the intensity of an ALA-untreated sample at 635 nm to adjust the data for different gain settings. The area under the curve, sensitivity, and specificity after adjustment were 0.74, 73%, and 63%, respectively. Some control cases that showed no peak at 635 nm were diagnosed as positive because of a difference between the sample treated and not treated with ALA; in these samples, the difference at 635 nm was detected in the range of 550 nm to 700 nm (Fig. 3b). To solve this problem, the difference between the intensity of ALA-treated and ALA-untreated samples at 600 nm was subtracted from the difference between the intensity of ALA-treated and ALA-untreated samples at 635 nm (Fig. 3a and b). After that, the adjusted difference was divided by the intensity of the ALA-untreated sample at 635 nm. This adjusted change ratio was used for the diagnosis of bladder cancer (the method of ALA-induced fluorescence cytology). |

| Animal Protocol |

Porphyrin analysis [4] The analysis was carried out according to Chisolm and Brown with the following modifications: the tissues were suspended in sterile water ( 1: 10 wt./vol.) and homogenized in a tissue grinder [ 2 11. To 100 ~1 of this homogenate the following were added: 700 p,l HCl 2 mmol/l and 800 p,l ethyl-acetate/glacial acetic acid (3: 1). After 10 min centrifugation at 18OOg, the ethyl-acetate phase with some protein is removed, and after a second centrifugation for 5 min at 1800g the HCl phase is measured in an LS 5B fluorescence spectrometer using a red-sensitive photomultiplier at an excitation wavelength of 410 nm and an emission wavelength of 650 nm. Although porphyrins are commonly determined by emission at 60 1 nm, under the conditions described, Protoporphyrin IX/PpIX has also a specific emission at 650 nm, which is about 80% of the emission at 601 nm and can be easily detected using a redsensitive photomultiplier. In our experience, bile acids in duodenal aspirates, and to a lesser extent other tissues, contain fluorophores with high emission at lower wavelength, which gave rise to interference in porphyrin quantitation at 601 nm. Emission at 650 nm in a direct extraction assay as described above was found to be proportional to Protoporphyrin IX/PpIX quantification, determined by a limited number of HPLC porphyrin separations. Porphyrin standards were analysed separately for their actual concentration using UV spectroscopy and the molar extinction coefficient ( .sdo7 = 0.275 L mol-’ cm-‘). Recovery of porphyrins was checked by adding standard Protoporphyrin IX/PpIX to the samples. A recovery between 90 and 100 was achieved. |

| ADME/Pharmacokinetics |

This study focalized on three PSs that are used clinically (PpIX and PF) or for in vivo experiments (PPa). Our team proposed PPa coupled to folic acid to treat ovarian metastases by PDT (Patent WO/2019/016397).

By analyzing the photophysical properties of these three PSs in different conditions, we highlighted the fact that each PS is unique and reacts very differently depending on its chemical structure and concentration. If the change of the medium polarity does not greatly affect the UV-visible absorption spectrum of PF, there is a drastic change for PpIX and PPa. In the literature, it is often claimed that PpIX should be excited at 630 nm in vitro or in vivo. This excitation wavelength is based on the absorption spectrum in ethanol. In FBS and PBS, which are aqueous media more similar to physiological media, the QI band is located at 641 nm. Depending on the localization of the PS in the cells, the local viscosity can be very different. We could also observe that modifying the solvent viscosity did not greatly affect the maximal wavelengths of absorption of QI in PpIX and PF but it was blue-shifted for PPa for 10 nm (from 678 nm to 668 nm). Temperature change slightly affected the UV-visible absorption spectra of PpIX and PF but drastically modified the UV-visible absorption of PPa in the range of 10 to 40 °C. Finally, modifying pH also induced a shift of QI band for PPa of 25 nm (from 704 nm to 679 nm). Perhaps the most interesting results are the ΦΔ obtained in different solvents. Depending on the solvent, the values were totally different. In toluene, we could not detect any 1O2 whereas the ΦΔ were quite good for PpIX and PPa 0.68 and 0.49, respectively. In EtOH, the ΦΔ was 0.92, 0.53, and 0.80 for PpIX, PPa, and PF, respectively. If we switched to D2O, we could not detect any 1O2 of PpIX or PPa and the ΦΔ was 0.15 for PF. Moreover, in real-life applications, the PS is ideally in a cellular context. The presence of protein, lipid, and other biomolecules molecules will also affect the photophysics of the PS. This raised the question of what type of experiments and which solvent should be used in the solution when performing in vitro studies.[2] |

| Toxicity/Toxicokinetics |

71484 rat LD50 intravenous 240 mg/kg Drugs in Japan, 6(729), 1982 71484 mouse LD50 oral >5 gm/kg Drugs in Japan, -(1192), 1995 71484 mouse LD50 intraperitoneal 1029 mg/kg Drugs in Japan, 6(729), 1982 71484 mouse LD50 subcutaneous 1147 mg/kg Drugs in Japan, 6(729), 1982 71484 mouse LD50 intravenous 484 mg/kg Drugs in Japan, 6(729), 1982 |

| References |

[1]. Protoporphyrin IX induced by 5-aminolevulinic acid in bladder cancer cells in voided urine can be extracorporeally quantified using a spectrophotometer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2015 Jun;12(2):282-8. [2]. Photophysical Properties of Protoporphyrin IX, Pyropheophorbide-a and Photofrin® in Different Conditions. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021 Feb 9;14(2):138. [3]. Protoporphyrin IX fluorescence induced in basal cell carcinoma by oral delta-aminolevulinic acid[J]. Photochem Photobiol. 1998 Feb;67(2):249-55. [4]. 5-Aminolaevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX accumulation in tissues: pharmacokinetics after oral or intravenous administration[J]. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998 Jun 15;44(1):29-38. [5]. G-quadruplexes sense natural porphyrin metabolites for regulation of gene transcription and chromatin landscapes. Genome Biol. 2022 Dec 15;23(1):259. |

| Additional Infomation |

Protoporphyrin is a cyclic tetrapyrrole that consists of porphyrin bearing four methyl substituents at positions 3, 8, 13 and 17, two vinyl substituents at positions 7 and 12 and two 2-carboxyethyl substituents at positions 2 and 18. The parent of the class of protoporphyrins. It has a role as a photosensitizing agent, a metabolite, an Escherichia coli metabolite and a mouse metabolite. It is a conjugate acid of a protoporphyrinate and a protoporphyrin(2-). Protoporphyrin IX is a metabolite found in or produced by Escherichia coli (strain K12, MG1655). protoporphyrin IX has been reported in Homo sapiens and Turdus merula with data available. Protoporphyrin IX is a tetrapyrrole containing 4 methyl, 2 propionic and 2 vinyl side chains that is a metabolic precursor for hemes, cytochrome c and chlorophyll. Protoporphyrin IX is produced by oxidation of the methylene bridge of protoporphyrinogen by the enzyme protoporphyrinogen oxidase. Protoporphyrin IX is a metabolite found in or produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Background: We evaluated the feasibility of photodynamic diagnosis of bladder cancer by spectrophotometric analysis of voided urine samples after extracorporeal treatment with 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). Methods: Sixty-one patients with bladder cancer, confirmed histologically after the transurethral resection of a bladder tumor, were recruited as the bladder cancer group, and 50 outpatients without history of urothelial carcinoma or cancer-related findings were recruited as the control group. Half of the voided urine sample was incubated with ALA (ALA-treated sample), and the rest was incubated without treatment (ALA-untreated sample). For detecting cellular protoporphyrin IX levels, intensity of the samples at the excitation wavelength of 405 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer. The difference between the intensity of the ALA-treated and ALA-untreated samples at 635 nm was calculated. Results: The differences in the bladder cancer group were significantly greater than those in the control group (p < 0.001). These differences were also significantly greater in patients with high-grade tumors than in those with low-grade tumors (p = 0.004), and also in patients with invasive bladder cancer than in those with noninvasive bladder cancer (p = 0.007). The area under the curve was 0.84. Sensitivity and specificity of the method were 82% and 80%, respectively. Conclusions: We demonstrated that protoporphyrin IX levels in urinary cells treated with ALA could be quantitatively detected by spectrophotometer in patients with bladder cancer. Therefore, this cancer detection system has a potential for clinical use.[1] Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an innovative treatment of malignant or diseased tissues. The effectiveness of PDT depends on light dosimetry, oxygen availability, and properties of the photosensitizer (PS). Depending on the medium, photophysical properties of the PS can change leading to increase or decrease in fluorescence emission and formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) especially singlet oxygen (1O2). In this study, the influence of solvent polarity, viscosity, concentration, temperature, and pH medium on the photophysical properties of protoporphyrin IX, pyropheophorbide-a, and Photofrin® were investigated by UV-visible absorption, fluorescence emission, singlet oxygen emission, and time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopies.[2] Background: G-quadruplexes (G4s) are unique noncanonical nucleic acid secondary structures, which have been proposed to physically interact with transcription factors and chromatin remodelers to regulate cell type-specific transcriptome and shape chromatin landscapes. Results: Based on the direct interaction between G4 and natural porphyrins, we establish genome-wide approaches to profile where the iron-liganded porphyrin hemin can bind in the chromatin. Hemin promotes genome-wide G4 formation, impairs transcription initiation, and alters chromatin landscapes, including decreased H3K27ac and H3K4me3 modifications at promoters. Interestingly, G4 status is not involved in the canonical hemin-BACH1-NRF2-mediated enhancer activation process, highlighting an unprecedented G4-dependent mechanism for metabolic regulation of transcription. Furthermore, hemin treatment induces specific gene expression profiles in hepatocytes, underscoring the in vivo potential for metabolic control of gene transcription by porphyrins. Conclusions: These studies demonstrate that G4 functions as a sensor for natural porphyrin metabolites in cells, revealing a G4-dependent mechanism for metabolic regulation of gene transcription and chromatin landscapes, which will deepen our knowledge of G4 biology and the contribution of cellular metabolites to gene regulation.[5] |

Solubility Data

| Solubility (In Vitro) | May dissolve in DMSO (in most cases), if not, try other solvents such as H2O, Ethanol, or DMF with a minute amount of products to avoid loss of samples |

| Solubility (In Vivo) |

Note: Listed below are some common formulations that may be used to formulate products with low water solubility (e.g. < 1 mg/mL), you may test these formulations using a minute amount of products to avoid loss of samples. Injection Formulations (e.g. IP/IV/IM/SC) Injection Formulation 1: DMSO : Tween 80: Saline = 10 : 5 : 85 (i.e. 100 μL DMSO stock solution → 50 μL Tween 80 → 850 μL Saline) *Preparation of saline: Dissolve 0.9 g of sodium chloride in 100 mL ddH ₂ O to obtain a clear solution. Injection Formulation 2: DMSO : PEG300 :Tween 80 : Saline = 10 : 40 : 5 : 45 (i.e. 100 μL DMSO → 400 μLPEG300 → 50 μL Tween 80 → 450 μL Saline) Injection Formulation 3: DMSO : Corn oil = 10 : 90 (i.e. 100 μL DMSO → 900 μL Corn oil) Example: Take the Injection Formulation 3 (DMSO : Corn oil = 10 : 90) as an example, if 1 mL of 2.5 mg/mL working solution is to be prepared, you can take 100 μL 25 mg/mL DMSO stock solution and add to 900 μL corn oil, mix well to obtain a clear or suspension solution (2.5 mg/mL, ready for use in animals). Injection Formulation 4: DMSO : 20% SBE-β-CD in saline = 10 : 90 [i.e. 100 μL DMSO → 900 μL (20% SBE-β-CD in saline)] *Preparation of 20% SBE-β-CD in Saline (4°C,1 week): Dissolve 2 g SBE-β-CD in 10 mL saline to obtain a clear solution. Injection Formulation 5: 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin : Saline = 50 : 50 (i.e. 500 μL 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin → 500 μL Saline) Injection Formulation 6: DMSO : PEG300 : castor oil : Saline = 5 : 10 : 20 : 65 (i.e. 50 μL DMSO → 100 μLPEG300 → 200 μL castor oil → 650 μL Saline) Injection Formulation 7: Ethanol : Cremophor : Saline = 10: 10 : 80 (i.e. 100 μL Ethanol → 100 μL Cremophor → 800 μL Saline) Injection Formulation 8: Dissolve in Cremophor/Ethanol (50 : 50), then diluted by Saline Injection Formulation 9: EtOH : Corn oil = 10 : 90 (i.e. 100 μL EtOH → 900 μL Corn oil) Injection Formulation 10: EtOH : PEG300:Tween 80 : Saline = 10 : 40 : 5 : 45 (i.e. 100 μL EtOH → 400 μLPEG300 → 50 μL Tween 80 → 450 μL Saline) Oral Formulations Oral Formulation 1: Suspend in 0.5% CMC Na (carboxymethylcellulose sodium) Oral Formulation 2: Suspend in 0.5% Carboxymethyl cellulose Example: Take the Oral Formulation 1 (Suspend in 0.5% CMC Na) as an example, if 100 mL of 2.5 mg/mL working solution is to be prepared, you can first prepare 0.5% CMC Na solution by measuring 0.5 g CMC Na and dissolve it in 100 mL ddH2O to obtain a clear solution; then add 250 mg of the product to 100 mL 0.5% CMC Na solution, to make the suspension solution (2.5 mg/mL, ready for use in animals). Oral Formulation 3: Dissolved in PEG400 Oral Formulation 4: Suspend in 0.2% Carboxymethyl cellulose Oral Formulation 5: Dissolve in 0.25% Tween 80 and 0.5% Carboxymethyl cellulose Oral Formulation 6: Mixing with food powders Note: Please be aware that the above formulations are for reference only. InvivoChem strongly recommends customers to read literature methods/protocols carefully before determining which formulation you should use for in vivo studies, as different compounds have different solubility properties and have to be formulated differently. (Please use freshly prepared in vivo formulations for optimal results.) |

| Preparing Stock Solutions | 1 mg | 5 mg | 10 mg | |

| 1 mM | 1.6485 mL | 8.2424 mL | 16.4848 mL | |

| 5 mM | 0.3297 mL | 1.6485 mL | 3.2970 mL | |

| 10 mM | 0.1648 mL | 0.8242 mL | 1.6485 mL |